Jewish Community

The Erfurt Jewish Community first appears in the historical record in the late 11th century, with the earliest recorded building of the Old Synagogue dating from around that time.

There is more detailed evidence from the 13th century. We learn from tax lists and deeds that Erfurt Jews worked in banking, and dealt not only with local towns and aristocrats, but had business relationships across the Holy Roman Empire.

Their residential neighbourhood was in the immediate city centre, in the quarter between the town hall, Krämerbrücke and Michaeliskirche. Here they lived in close proximity with Christian merchants and here stood their representative synagogue. Close by was a mikveh, a Jewish ritual bath. The cemetery was outside the residential area at Moritztor.

Eminent scholars lived and taught in Erfurt. Evidence for the developed intellectual life are 15 Hebrew manuscripts that belong today to the Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage. Preeminent amongst the scholars was the rabbi and author Alexander Süßkind ha-Kohen. He worked in Worms, Cologne, Frankfurt and in his birthplace Erfurt, where he was probably murdered on 21 March 1349 during the plague pogrom.

The wave of Jewish persecutions, which spread with the plague from Southern Europe northwards and westwards, reached Erfurt in March 1349. The persecutors were motivated by, amongst other things, over-indebtedness, hatred of non-Christians as well as professional jealousy, but also political considerations played a part. The accusation that Jews had been poisoning wells, thus causing the plague, was a welcome excuse for violence. During the pogrom on 21 March 1349 the whole Jewish community of Erfurt was destroyed and up to 900 people died. A merchant subsequently converted the Old Synagogue into a storehouse.

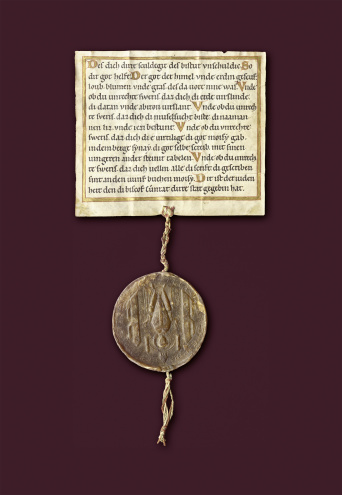

A short time later, probably from 1354, Jews became resident in Erfurt again. The Erfurt Council had a synagogue built behind the town hall between 1355 and 1357 for the new community. The Jews lived to a large extent in the same quarters, but now for the most part in rented accommodation in municipal “Jews houses”. There were also in this second settlement some very wealthy and influential families who worked in overseas trade and finance. Numerous poorer Jews lived from pawn broking, trading and the manufacture of shofars, a ram’s horn which is blown on holy days. In the 15th century anti-Jewish sentiment was growing in Erfurt. In 1453 the municipal council revoked the protection of the Jews, and all Jews left the town around this time. Since the year 1454 Jews were no longer tolerated in Erfurt. The Jewish dwellings were sold, the synagogue was converted into an armoury and the cemetery was razed.